Clinical studies should have appropriate risks management measures, and clinical trials require liability insurance to protect patients in the event that something goes wrong. For more information on how to assess risk, view the resources on the 'Risk Assessment' section of the ProcessMap.

In recent years there have been large claims made on Pharma companies due to negligence, leading to huge payouts. Examples include claims brought against the drug manufacturer, Pfizer regarding the testing of the antibiotic, Trovan for treatment of Meningitis epidemic in 1996 in Nigeria. 11 Children died and about 200 patients were injured. Investigations revealed that the researchers did not obtain signed consent forms and parents were not told that the medication being administered was experimental drug. Also the comparator arm of the study was a sub-standard dose of antibiotics.

Another case was seen with the drug manufacturer, TeGenero AG who carried out a Phase1 study; testing the drug TGN1412 in a first-in-man study. Six out of the eight patients taking part in the study suffered multiple organ failure. The other two were placebo subjects. The company had to pay out on claims made by the subject and went insolvent as further investment could not be secured.

There are a number of liabilities involved in clinical studies and the type of cover required is dependent on the type of research, the risk, who the sponsor is and their regulatory obligation (as dictated by international and regulatory requirements), and where they are situated.

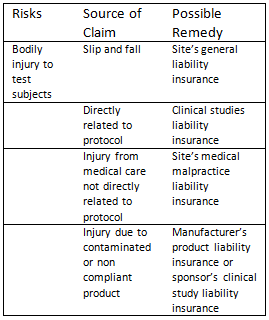

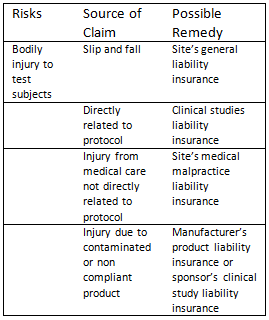

Some of these include public, product and professional liabilities. Other types of liability which may directly or indirectly be applicable to clinical studies include employers’ liability, clinical studies medical malpractice liability etc. The table below depicts risks and possible liability that will need to be in place to remedy those risks:

The Global nature of Clinical Studies Agreement

The global nature of clinical studies requires that investigators and sponsors must deal with multiple legal jurisdictions, with differing laws and regulations. These rules establish expectations based on each party’s locale and could limit the flexibility of investigators (i.e., research sites) when negotiating clinical study agreements (CTAs).

The rules governing an agreement are usually on multiple levels such as international (including multinational), national, state, institutional and societal influences.

International

Various international bodies define rules for clinical research such as the Nuremberg Code, Declaration of Helinski, and the International Conference on Harmonization ICH E6 Guideline for Good Clinical Practice but these are “guidelines” and are not enforceable. It is partly why the EU clinical directive, and the Mercosur (Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil) have published extensive laws for their member states to adopt into their national law. Studies run in these regions must therefore adhere to these laws and a breach could mean persecution or significant fine to companies if found liable.

National

There are obviously national laws that govern the conduct of clinical research in each country and rules that some countries consider important may be absent in other countries. For instance India amended its drug laws in 2004 so that phase I safety studies cannot be conducted in the country for drugs developed outside of India. In practice, levels of reporting, auditing and enforcement may vary widely, with none at all apparent in some countries.

State and Province

Some states (in countries that have state-owned laws) may have their own laws that specifically or incidentally govern clinical research. Again, the laws may vary from place to place, thereby making it difficult to track or manage.

Institutions

The institution where the study is to be carried out may place specific requirements on funding which may originate from the entity’s idiosyncratic interpretation of the laws, which can be ambiguous. For instance some hospitals will not allow wired internet connection of external devices in order to safe guard their liability in terms of data protection.

Societal

The customs of a society may also have an effect on the laws governing clinical studies. Concepts of personal privacy, for example, may be problematic in societies where the individual is subordinate to the extended family.

A study may be subject to conflicting laws, even if the sponsor and investigator are in the same legal jurisdictions. These conflicts are normally resolved by priority of law, e.g., national laws override state laws, but it may not always be straightforward to untangle (or remember) overlapping conditional requirements, authorizations and prohibitions.

Clinical Study Agreement (CTA)

Clinical study agreements are very helpful legal documents that should set out all the arrangements in place for studies being conducted between different groups or across different sites. However, executing them can be quite a challenge, especially when dealing with large multinational studies. There are many different parties involved in the process and a variety of laws, regulations, languages, cultures, social and historical backgrounds to take into consideration. Always leave more time than you think you need to get a CTA agreed!

Generating the Contract

All CTAs have certain provisions in common (e.g., confidentiality, rights to publish clinical results, indemnification, ownership of clinical data, ownership of inventions, choice of law, etc.). Although the common provisions appear in all CTAs, each provision can be drafted so as to give rise to several different rights and obligations of the parties. For instance in the provision regarding ownership of inventions generated by sites, the contract could be drafted such that the sponsor owns all the rights, jointly share the rights or site owns the rights they create.

Reasons for CTA Delays

Country and topic-specific knowledge

Delays often occur because of a lack of knowledge on applicable local laws and regulations. For instance, planning the contract negotiation process in the months of July and August can be very difficult in majority of countries in Southern Europe, due to the long holiday season; or in January in Southern Africa. Some sites will insist that the prevailing law should be the country where the site is based for the agreement to be enforceable. In Australia and Singapore, a local company must provide sponsor’s indemnification.

A contract manager should therefore be fully aware of these issues or must have access to someone knowledgeable about local requirement.

Such awareness is necessary so that a proper risk assessment can be made and a pragmatic approach applied.

Adequate Resources

It is important that sufficient, qualified staff, possessing the required skills and experience, is available to move the contract process forward. It is not easy to find qualified staff and this is compounded by the fact that the workload in this area can fluctuate considerably, due to varying life cycles of clinical study process. The use of external resources for dealing with site agreements could be a viable and more cost effective solution. This is particularly relevant for relatively smaller institutions where a limited number of studies are conducted at a time.

The other advantage of an external resource is that it could offer flexibility and the required expertise when needed.

Country and local specifics

Demanding country-specific procedures, laws, and regulations, or bureaucracy at sites is harder to avoid. In such cases, it might be useful for local organizations that promote clinical research in their country to use their influence to push for a more efficient process.

Translations

In many countries, site agreements will need to be translated into the local language. The reasons for these range from the fact that it could sometimes be for information purposes, sites unwillingness to sign a contract in another language or it may be because it is a legal requirement. Entire templates and larger pieces of text in an agreement under negotiation could be translated by certified translators while small parts can be translated by local clinical staff into and from their native language. This approach is a pragmatic one; as small words can make a considerable difference in legal meaning. It therefore, might be prudent to consider using a certified translator in all cases except for purely administrative parts such as names and addresses. Proper translations of the contracts are important not only because of the risk of committing to contents that was not intended, but also because unnecessary delays may occur in clarifying text. For example, a party may reject certain terms that would have been absolutely acceptable had they been properly translated.

For practical advice about how to find qualified translators and commission work see the article https://globalhealthtrials.tghn.org/articles/back-translation-clinical-trial-documentation-informed-consent-forms/

Improving the Contract Process

Industry research indicates that contract and budget negotiation and approval causes 38% of clinical study delays, and legal review causes another 24%. This results in millions of dollars in cost-overruns and lost potential revenues. In academic settings investigators also report that getting legal agreements in place can be one of the slowest steps they face in setting up a new study.

Contract Template

The contract template can have a tremendous influence on the speed and success of the negotiation process. A complicated and unclear template makes hospitals and investigators reluctant to review and agree the terms of the contract. On the other hand, a well-structured, straight-forward template will inspire confidence and trust with the hospitals and investigators.

Making use of an existing CTA would be an excellent start, especially for academic groups who may not have much previous experience. Most research offices have examples of previous agreements and these would be a good starting point.

Having a standardised CTA may be a better and quicker option. In the United Kingdom for instance, the involved interest groups successfully introduced a standardised template for clinical study agreements which is proving to be successful because, the template was created jointly by the representatives of the parties involved in clinical research, the template is of high quality and also leaves room for flexibility

Indemnity

Clinical trials should have some form of indemnity (insurance, protection) in place to compensate participants for any unforeseen adverse outcomes arising from the interventions or medical negligence (deviation from the protocol). This does not include compensation for outcomes related to the condition being studied nor (usually) to risks clearly outlined in the informed consent process. For more information on this step, see ‘Organise appropriate insurance’.

Conclusion

Over the last number of years, it was the regulatory and Ethics approval processes that took so long in setting up studies. Even though there are still some delays in some countries, this process has progressed significantly in recent years. The contract negotiation process which is also pertinent to setting up studies has however not had the same attention as the regulatory or Ethics process; possibly due to the fact that it is deemed a local rather than a global issue or that industry experts are resigned to the fact that not much can be done to improve the process. It is hoped however, that some of the ideas presented in this article will help identify and improve this compulsory legal step and consequently the start up time of clinical studies

References

What is Clinical Study Insurance

http://www.med.hku.hk/images/document/04research/institution/HAWorkshop2012_09_Clinical%20Trial%20Insurance_AndyWong_120110.pdf

Laws, Regulations and Clinical Study Agreements

http://firstclinical.com/resources/articles/Laws.pdf

Mikhail S and Giddings R “Clinical Contracting Efficiency” Applied Clinical Studys 2011

http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/clinical-contracting-efficiency

Parishwad R “Indian Supreme Court’s Anger Over Unregulated Clinical Studys” 2013

http://www.rsc.org/chemistryworld/2013/01/india-supreme-court-unethical-clinical-studys

Rijswijk-Trompert M “Clinical Study Agreement Negotiations” Applied Clinical Studys 2012

http://www.appliedclinicalstudysonline.com/appliedclinicalstudys/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=776904&sk=&date=&pageID=5

Print all information